There are two stories here.

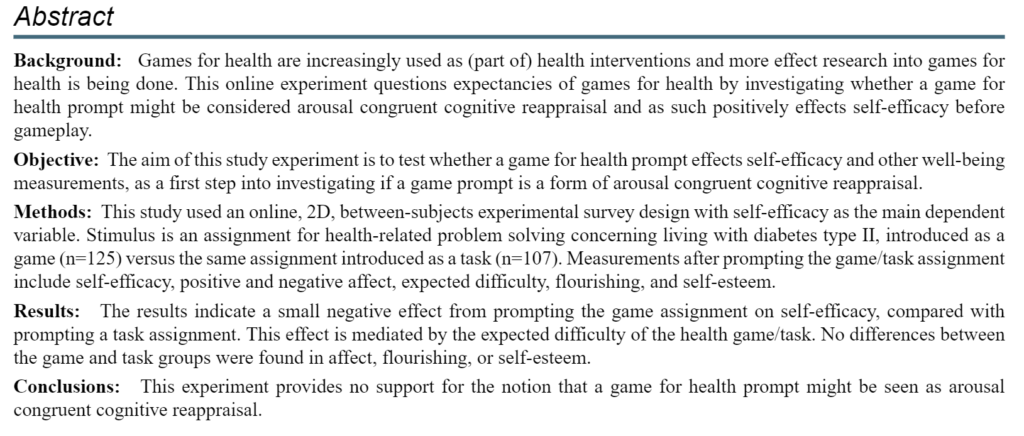

One is the story of the content of the paper and this is pretty straight forward. It started reading a paper and wondering about something:

“…reading the work of Brooks, it seemed to me that prompting a game for health is also a call to be excited amidst anxious content and I wondered if a game for health might be considered arousal congruent cognitive reappraisal? If so, this perspective could help to explain some of the attraction to games for health and their effects on self-efficacy.”

Diving into this question I found out more about cognitive reappraisal and self-efficacy and even found a diabetes specific self-efficacy scale (not in paper). I found more work and interesting examples of games for health and well-being. While investigating measurements for well-being I found a Flourishing scale. When I thought I had a good idea of the relevant concepts and their measures I formulated a simple online experiment. I ran it, analysed it and wrote up the process. It felt so good to throw my considerations at reality and collect data. I dipped my toes in the micro-task market by using MTurks. There was some struggling and getting to grips with mediation analysis. I was surprised – and initially very frustrated – by the answer to my overall question and am very grateful that I included a measure that might offer an explanation for these unexpected responses. The results offer a minute contribution to the better understanding of using games for health. Please read it and let me know what you think https://games.jmir.org/2021/1/e20209/

Then there is a second story of the emotional context of this paper. This centres around a PhD that did not end well. When this paper was in a very early stage, I quit the PhD. This was a hard decision but I had lost all faith in ever getting to a positive ending and I still think it was the right decision. However, letting go of what I had been holding onto meant I fell down further. Chronic pain, depression, physical therapy, mindfulness based cognitive behavioural therapy, a lovely psychologist at the pain clinic all followed each other. A process taking over two years. Starting during my PhD and ending long after.

And somewhere on my computer and nagging in the back of my mind was this paper. Sort of finished – but unpolished. Hours of my life already in it, the effort of all the people that had participated already in it and the method/experiment/result simple truths regardless. It’s not the ideas, the experiment or the correlations fault. What I love about science – and chase in effect research – is something that exists above, beyond and outside of me.

But every time I opened this document waves of emotion came with it. Even so, I returned to work on these pages. First this was a great smack in my face. None of the statistical analysis were clear in my mind and my ability to focus was shredded. This confrontation with a new me that could no longer understand the old me was horrible. Over time and a lot of emotions I re-read and re-did my own work until I re-understood. Then I tried to improve the paper.

Thankfully, I have some amazing friends. One is a health researcher and a data wizard, one is a statistician for social sciences and one is a games researcher. I worked on the pages until I thought they were good enough to be shown. My friends read it and returned it to me with comments. Normal comments that made it better – no fundamental flaws, nothing crazy. All three told me they thought it was about one-round-of-improvements away from trying to get it published. I took all their comments and made it better.

Now, there is almost four years in between me ending the PhD and me sending this paper in to be judged by JMIR Serious Games. The first year-and-a-half I didn’t touch it. Another year of painfully and sporadically confronting myself with myself and then a long time of working on it in between the rest of life. A life that has nothing to do with academia anymore. After submission, another year follows that includes a revise-and-resubmit, a global pandemic and an editor-switch before getting it published in my first-choice journal.

Five years and such a long emotional journey for such a small, simple paper.