Play seems to be something unreal. At first it seems intuitively clear what is meant by play; it is obvious when one is playing and when one is in earnest. The distinction between real and play seems clear, but at closer inspection the concept of play reveals itself to be a complex one. Before a very specific type of game play can be discussed, a definition of play in general must be given.

Caillios (1957) defines play as an activity that is essentially free, separate, uncertain, unproductive, governed and make-believe. Meaning that we cannot be forced into play; it is something we undertake by our own choice. If we would be forced, the experience would cease to be play and become an assignment. Furthermore, play is separated from normal day-to-day living. Often this separation is physical; one chalks lines on the ground for hop-scotch to physically limit the playing field or plays a board game on a board and only on this board does the game exist.

Caillios (1957) defines play as an activity that is essentially free, separate, uncertain, unproductive, governed and make-believe. Meaning that we cannot be forced into play; it is something we undertake by our own choice. If we would be forced, the experience would cease to be play and become an assignment. Furthermore, play is separated from normal day-to-day living. Often this separation is physical; one chalks lines on the ground for hop-scotch to physically limit the playing field or plays a board game on a board and only on this board does the game exist.

Play is also separated in time: there is a start and a stop to the playing. Play also requires some level of uncertainty; will it work, will it be fun, will the audience laugh and of course who will win? If the outcome of the undertaking was certain play would turn into a task. It would be no more than a series of steps to achieve an outcome. The achievement of an outcome must also be absent; the product of play can only be play itself, otherwise it becomes merely a means to an end. To control all the things play must or must not be, play requires rules. Finally, play can never be real. Huizinga sums it up as

“a free act, that is consciously ‘not meant’ and outside of normal life, that still might completely absorb the player, to which no direct material interest is connected, or use is gained, that unfolds itself in a purposely set up limited time and space, which adheres to certain rules and order, and brings forth a sense of community, which gladly shrouds itself in secrets or is distinguished from the real world by use of disguise.“ (translated from p. 41, Huizinga, 1938).

The definitions of Caillios (1957) and Huizinga (1938) both define play as a domain that is within society yet different from it, a domain which has no merit beyond itself, in which chance is always of influence in a complex structure governing the fantasy of which the domain is created and a domain to which one must enter voluntarily. An important part of play is the interaction; with oneself but often in a social setting. “Playing is always communication” (Ohler, 2008, p. 3638), whether this is intra- or interpersonal communication. These definitions give a solid structure to hold the fuzzy concept of play.

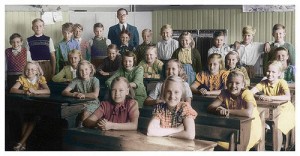

The way we play might differ between cultures but there is not one culture in which play is absent (Huizinga, 1938). We engage in play to fulfil a number of basic human needs. Based on Self Determination Theory, Ryan and Deci (2000) attribute three fundamental needs to every human being; a need for competence, a need for autonomy and a need for relatedness. When these needs are met psychological well-being is heightened and self-motivation is increased. By playing these needs can be met. The need for competence is fulfilled by a task not too challenging but not too simple so one can feel competent, which relates to the concept of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). The need for autonomy is met by one of the ‘ground rules’ of play; that it is voluntarily. The player autonomously decides to play. The relatedness we find in the social aspects of play, most playing is done in a social interaction. Be it between several players, between a player and an audience or between a player and a mediated character.

“Play is a credible developmental and evolutionary antecedent to the more sophisticated forms of entertainment we engage in today” (Vorderer, Steen, & Chan, 2006, p. 13). One of the more sophisticated forms of play that we engage in today is interactive gaming. Gamers are a different type of media audience: Contrary to most audiences, they are active.

For the TV, radio or newspaper audience communication is mostly one-way and the users are passively on the receiving end of the medium (Katz, 1962). Games are a fixed part of the media landscape that we move in today; “…[games] are now considered main stream media, competing with newspapers, television, radio, and film for attention and dollars” (Williams, 2006, p. 199). Gamers and internet users search and demand content specific to their needs, interacting and possibly adapting it as they see fit. Creation of new content is also high among gamers. For example, almost a quarter of the popular MMORPG Everquest players had created their own artwork or fiction based on or around the game play (Griffiths, 2003).

Concepts such as curiosity, surprise and suspense work very different in interactive video games compared to other media entertainment and therefore most media enjoyment theories are not directly applicable to interactive gaming (Grodal, 2000). A likely more suitable perspective on the investigation of interactive media is a play-perspective. “The analysis of interactive media entertainment especially can be based on a play frame (Ohler, 2008, p. 3639)”.

References

Caillois, R. (1957). Le jeux et les Hommes [Man and play] (M. Barash, Trans.): University of Illinois press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow. New York: Harper and Row.

Griffiths, M., Davies, M., & Chappell, D. (2003). Breaking the stereotype: the case of online gaming. Cyberpsychology and behaviour, 6 (1), 81-91.

Grodal, T. (2000). Video games and the pleasures of control. In D. Zillmann & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Media entertainment: the psychology of its appeal (pp. 197-212). Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo ludens. Proeve eener bepaling van het spel-element der cultuur. In Verzamelde werken V. Cultuurgeschiedenis III (pp. 26-146).[Homo Ludens, Test of determination of the gaming-element of culture. In the Collected works of Cultural history III] Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon N.V.

Katz, E., & Foulkes, D. (1962). On the use of the mas media as “escape”: clarification of a concept. Public opinion quarterly, 26, 377-388.

Ohler, P. (2008). Playing. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The international encyclopaedia of communication (pp. 3638-3640): Blackwell publishing.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Vorderer, P., Steen, F., & Chan, E. (2006). Motivation. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of entertainment (pp. 3-18). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

Williams, D. (2006). A brief social history of game play. In P. Vorderer & J. Bryant (Eds.)

– this is an excerpt from my MSc-thesis How Alternate Reality Gaming changes reality –